El ex rehén de las FARC, Marc D. Gonsalves (izq.), junto a miembros de su familia en una conferencia de prensa donde los tres contratistas militares recién liberados pudieron hacer breves comentarios.

Con sus hijos, hermanos, cónyuges y padres en medio de lágrimas y aplausos, tres estadounidenses que estuvieron cautivos en manos de las FARC más de cinco años, denunciaron el lunes a sus captores, calificándolos de terroristas que los tuvieron encadenados del cuello en la selva.

La primera aparición pública desde que fueron rescatados el miércoles debía ser breve, pero Marc Gonsalves, uno de los liberados y vecino del sur de la Florida, pidió permiso a sus compañeros para salirse del programa.

Habló con emoción sobre las FARC, que lo tomaron de rehén junto con dos contratistas de defensa estadounidenses en febrero del 2003 cuando el avión en que viajaban se estrelló durante una misión antinarcóticos.

"Quiero contarles de las FARC'', dijo Gonsalves, hablando inicialmente en inglés y después en español. "Dicen que quieren igualdad. Dicen que quieren hacer de Colombia un mejor lugar. "Es una mentira. Son terroristas con mayúscula''.

Los tres contratistas --Gonsalves, Thomas Howes y Keith Stansell-- se presentaron en el Centro Médico Brooke del Ejército, donde reciben atención médica y sicológica desde que llegaron a San Antonio después del rescate por parte del Ejército colombiano.

Los tres se dirigieron a los medios pero no respondieron preguntas en el auditorio del centro, adornado con cintas amarillas y banderas estadounidenses. Estuvieron acompañados de numerosos militares que los mantenían alejados de los medios y de sus familiares. Vestidos de civil y con unas 30 libras menos que cuando fueron capturados, debían haber hecho una declaración breve de agradecimiento a sus familiares, a los gobiernos de Estados Unidos y Colombia y a su empresa, Northrop Grumman Corp., por su apoyo.

Pero Gonsalves habló con emoción largo y tendido.

Caracterizó a los rebeldes de narcotraficantes, extorsionistas y secuestradores que rechazan la democracia y le lavan el cerebro a sus seguidores. Agregó que la mayoría de los miembros de las FARC son colombianos jóvenes sin instrucción que apenas pueden leer o escribir.

"Los he visto llevar a un recién nacido en cautiverio, un bebé que necesitaba asistencia médica'', dijo Gonsalves en voz baja y emocionada. "En este momento hay más rehenes. En este exacto momento los están maltratando, están encadenados por el cuello y les apuntan con armas automáticas''.

"Yo mismo, y mis amigos Tom y Keith, hemos sido víctimas de su odio, de sus abusos y sus torturas'', dijo. "He visto incluso cómo se suicidan para evitar la esclavitud de las FARC''.

Howes, que cumplió 55 años el 4 de julio, fue el primero en hablar y lo hizo con reticencia, con un aspecto abrumado frente a docenas de medios de comunicación y personal militar.

"Hace casi cinco años y medio caí en un lugar extraño'', dijo. "Estamos bien, pero no podemos olvidar a los que quedaron atrás en cautiverio en la selva colombiana''.

Stansell, de 44 años, tenía en los brazos a sus hijos de 5 años, Nicolas y Keith Jr., a quienes vio por primera vez el fin de semana, y los besaba repetidamente. Su prometida colombiana, Patricia Medina, estaba embarazada cuando lo capturaron. Con una sonrisa de oreja a oreja, Stansell, visiblemente conmovido, hizo eco de los sentimientos de su amigo, agradeciéndole a su familia, su empresa y a los gobiernos por su rescate. "Ellos son la razón por la que estoy vivo'', dijo.

Los tres están en un proceso voluntario de readaptación a la vida normal, organizado por el Ejército y que se basa en las experiencias de los prisioneros de guerra de Vietnam. Parte de ese proceso incluye compartir y hablar de las experiencias vividas en cautiverio.

‘‘Uno nunca sabe cómo terminan estas cosas'', dijo James Pitts, presidente de Northrop Grumman, en una breve conferencia de prensa después que los tres contratistas salieron del auditorio. ‘‘Nuestros muchachos han mostrado mucho valor, mucho más de lo que el deber les exige''.

No se sabía cuánto tiempo permanecerán en Fort Sam Houston, pero un oficial militar dijo que será hasta que ellos quieran y que era absolutamente voluntario. Pitts declinó discutir las experiencias de los tres rehenes.

"Ellos lo contarán a su debido tiempo'', dijo. "Tienen una historia que contar y quieren hacerlo''. El director del equipo médico, el coronel Jackie Hayes, dijo que todas las pruebas médicas concluyeron que los tres gozan de buena salud, pero declinó ofrecer detalles.

El coronel Carl Dickens, jefe del equipo sicológico, dijo que la readaptación de los hombres a la vida normal es como si alguien que ha estado mucho tiempo en una habitación oscura y lo sacan a la luz. "Les ofrecemos un filtro para que puedan regresar a la normalidad'', dijo. "Son individuos muy resistentes y flexibles''.

El Nuevo Herald

http://www.elnuevoherald.com/167/story/239863.htmlFear for Colombian Hostages Still in Jungle

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — The nation is euphoric after intelligence agents rescued 15 hostages from the clutches of guerrillas last week, but for Magdalena Rivas, the outlook is not so bright.

Her son, Lt. Elkin Hernández Rivas, was a young police officer when FARC rebels snatched him a decade ago.

“They rescued the trophy hostages, but what about those still in captivity?” a despondent Ms. Rivas, 59, said in an interview.

She fears that his chances of coming home soon have been diminished by the spectacular ruse to trick the rebels and the resulting celebration of the hostage rescue.

Just a few months ago, the FARC sent her a “proof of life,” a short video of Lieutenant Hernández shot somewhere in the Andean jungle. It shows a man with hollowed cheekbones and a shaved head, looking wizened beyond his 33 years.

Lieutenant Hernández is one of 25 political captives still in the FARC’s hands, used as bargaining chips. Estimates vary, but at least 700 Colombians abducted for ransom, and perhaps more, are also thought to remain in the control of leftist guerrillas or criminals, including several hundred held by the FARC, as the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia is known.

The ransom paid to free some hostages is one of the FARC’s main sources of income; the other is cocaine trafficking.

The families of those captives, like Ms. Rivas, worry about the consequences of the rescue last week of Ingrid Betancourt, the French-Colombian politician, three American military contractors, and 11 members of Colombian security forces.

The operation, carried out by intelligence agents disguised as aid workers, journalists and guerrillas, has already shaken the foundations of Colombian politics. President Álvaro Uribe’s approval ratings stand at almost 90 percent, leading to talk of a bid for a third term.

Ms. Betancourt, abducted six years ago while campaigning for president, has also not ruled out a return to politics at the highest level in Colombia.

With the rescue behind it, Colombia, its newscasters and editorialists proclaim, is on the march again. The political aftermath of the rescue is resonating throughout the country and threatening to eclipse the concerns of the families of those who remain captive, the families say.

At Ms. Rivas’s living room in Centenario, a grim residential district far from the skyscrapers and manicured restaurants of north Bogotá, the walls are filled with photos of her son, including one showing him in his police uniform at age 21. Another memento, his diploma from the General Santander School for Cadets, hangs nearby.

“When the news of the rescue emerged, I cried, then prayed to God, then cried again asking if this was punishment for not praying well enough,” said Ms. Rivas, a homemaker.

“I know my son isn’t a trophy,” said Ms. Rivas, gathering her composure. “But I demand to have him back.”

Each Tuesday morning, Ms. Rivas treks to the Plaza Bolívar here together with other relatives of FARC captives. Their group, called Asfamipaz, represents family members of kidnapped police officers and soldiers. At their weekly vigil, they attempt to remind the rest of Colombia of their plight.

“It would have been a decent gesture last week for the government to inform our members that they are still working on our behalf, or maybe offer some psychological help,” said Marlene Orjuela, director of the group. “But we have heard nothing, just official silence,” she said.

María Teresa Mendieta waited five years to hear from her husband, Lt. Col. Luis Mendieta, whose first letters from captivity came out of the jungle with captives freed in January. She attended a Catholic Mass here on Monday to commemorate the rescue of the other captives.

“I dreamed that I could also have the chance to hug my husband and see him in freedom,” Ms. Mendieta said as she left the service.

Uncertainty persists over the fate of the FARC’s captives while the dynamics shift surrounding efforts to negotiate with the rebels. Ms. Betancourt has offered to press the FARC to free more hostages, telling Ms. Rivas and other relatives as much at a meeting here last week.

On Monday, Ms. Betancourt sent a message of solidarity to the remaining hostages on the Spanish-language service of Radio France International. At the same time she called on Mr. Uribe to soften his tone with the guerrillas.

“Uribe, and not only Uribe but all of Colombia, should also correct some things,” she said. “We have reached the point where we must change the radical, extremist vocabulary of hate, of very strong words that intimately wound the human being.”

Mr. Uribe, a staunch ally of the Bush administration, has not ruled out seeking a third term, but doing so would be most likely to ignite conflict within Colombia’s political establishment.

Mr. Uribe’s government also said Monday that it preferred to negotiate directly with the FARC, effectively cutting out foreign mediators, after Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos said evidence had surfaced on FARC computer files recovered in March that a Swiss emissary may have carried $500,000 for the FARC to Costa Rica.

While basking in the triumph of their rescue operation, Colombian authorities said they would still work for the release of other captives, though without offering details. “We don’t think the FARC would take action against them,” Mr. Santos said of the remaining two dozen political hostages.

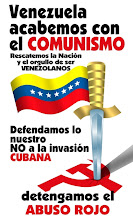

Public support for the FARC among prominent leftists outside Colombia is also diminishing, potentially opening a window for the group’s new leaders to soften their policies after the recent death of their top commander, Manuel Marulanda.

Echoing earlier comments by President Hugo Chávez of Venezuela, the former Cuban president, Fidel Castro, called over the weekend for the FARC to unconditionally release all of the hostages, saying, “Civilians never should have been kidnapped, nor the soldiers kept as prisoners in jungle conditions.”

The FARC, of course, hews to its own methods of give-and-take, as does the National Liberation Army, or E.L.N., a smaller leftist insurgency.

The FARC still carries out abductions, though its ability to do so in large cities like Bogotá and Medellín has been sharply curtailed in recent years. Yet while kidnappings in Colombia have dropped, abductions have surged in neighboring Venezuela, where both groups operate with relative ease in border areas.

“It is very premature to say we’re going to arrive at a peace process with the FARC,” said Olga Lucía Gómez, director of the País Libre Foundation, a group here that counsels kidnap victims. In the meantime, Ms. Gómez said, “There is still discrimination in which some victims are made to appear more important than others.”

The disconnect between the famous hostages rescued last week and the largely obscure captives remaining with the FARC is not lost on Gustavo Moncayo, the father of a soldier kidnapped 11 years ago.

Mr. Moncayo, 56, walked 600 miles from his town in southern Nariño Province to Bogotá to call attention to his son’s captivity.

Mr. Moncayo said his hopes for a negotiated release of his son and other captives had dimmed in recent days. “The humanitarian effort will be made harder because this operation generates distrust,” he said. “How are we going to ask international groups to collaborate with us and for the FARC to accept them when they have been fooled?”

The New York Times

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/07/08/world/americas/08colombia.html?_r=1&hp&oref=slogin

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario